application containerization (app containerization)

What is application containerization (app containerization)?

Application containerization is a virtualization technology that works at the operating system (OS) level. It is used for deploying and running distributed applications in their own isolated environments, without the use of virtual machines (VMs). IT teams can host multiple containers on the same server, each running an application or service. The containers access the same OS kernel and use the same physical resources. Containers can run on bare-metal servers, virtual machines or cloud platforms. Most containers run on Linux servers, but they can also run on select Windows and macOS computers.

Application containerization benefits and drawbacks

Organizations of all sizes have been turning to application containerization because of the many advantages it offers over more traditional application deployments on bare metal or within VMs. Here are some of the more commonly cited benefits:

- Efficiency. Containers share the host's kernel and resources, resulting in very lightweight container instances. As a result, containers require fewer CPU, memory and storage resources compared to traditional application deployments. With the reduced overhead, the same underling infrastructure can support many more containers.

- Portability. If the OS is the same across environments, an application container can run on any system or cloud computing platform without requiring code changes. There are no guest OS environment variables or library dependencies to manage.

- Agility. Containers are lightweight, portable and easily replicated, making them well-suited for automation and DevOps methodologies. Throughout the application lifecycle -- from code build through test and production -- the file systems, binaries and other information stay the same. All the development artifacts are consolidated into one container image. Version control at the image level replaces configuration management at the system level.

- Scalability. After a development team has built its container images, they can generate container instances quickly, taking advantage of automation and orchestration tools. That lets them deploy applications based on current workload requirements, while being able to easily accommodate future fluctuations in application loads.

- Isolation. Containers run in isolation from each other. If a problem occurs in one container, it will not impact another container or the host system itself. In some cases, an application will span multiple containers, as with microservices. If a problem arises in one of those containers, developers can focus their remediation efforts on that container without bringing down the rest of the application.

- Speed. Because containers are so lightweight, they can be created and started in little time, much more quickly than with virtual machines. They rely on the host's kernel, so there is no OS to boot up, and they contain all the dependencies needed to run the application. In this way, they can be deployed as soon as they're needed, wherever they're needed, with much of the process automated.

To a certain degree, containerization can help improve security because applications are better isolated than when they run on bare metal. Containers are also protected by policies that dictate their privilege levels. Even so, security remains one of the top concerns of containerization.

Containers are not isolated from the core OS, so they can be susceptible to threats to the underlying system. At the same time, if a container is compromised, the attacker might also penetrate the host system. In general, security scanners and monitoring tools are better at protecting a hypervisor or OS than they are containers.

Another challenge is that application containerization is a relatively new technology that is still rapidly evolving. Although the technology has matured in recent years, it is still a relatively new concept for some IT and development teams. They might lack the knowledge and skills necessary to implement containers efficiently and securely.

This problem can be exacerbated by trying to implement containers across multiple environments or even on multiple host operating systems. Not only must IT contend with the complexities of orchestrating the containers across environments, but they might also need to deploy additional layers of abstraction.

For example, if they want to run their Linux containers on Windows machines, they might choose to set up one or more virtual machines that are running Linux. The additional layers add complexity to the implementation, making it more difficult to deploy, secure and monitor the containers, potentially undermining some of the advantages of using containers.

How application containerization works

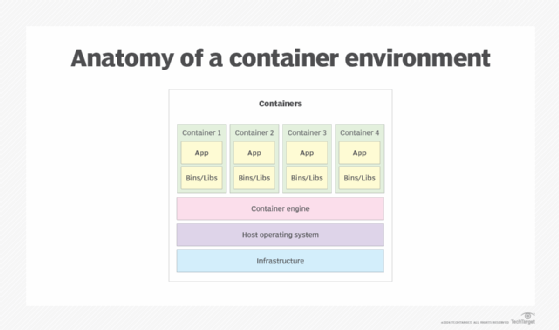

The architecture of a containerized environment relies on multiple components that work together to create, start, stop and remove containers. Figure 1 shows a high-level overview of the core architecture, with the containers sitting at the top of the stack and the infrastructure at the bottom, serving as the foundation for the entire system.

The following components make up to core architecture of a containerized environment:

- Infrastructure. Like most computing environments, a hardware layer is needed for running the host OS, which supports the rest of the components. The infrastructure is often made up of commodity hardware.

- Host operating system. The OS runs on the hardware infrastructure, providing an operating environment for the other components. The containers rely on the OS kernel to run their applications. Most containerized environments use Linux for the OS.

- Container engine. The container engine is a software program that runs on top of the host OS, leveraging its kernel for the container instances. The container engine provides a runtime environment for the containers. It also manages the containers and provides the resources they need to run their applications. Docker is the most popular container engine in use today.

- Container. A container is an instance of a container image. It includes the components necessary to run the container's application or service. The components can include binaries and libraries (bins/libs) as well as environment variables and other files.

A container is an instance of a container image that is created at runtime. A container image serves as a template for creating one or more container instances as they're needed. The image is a self-contained package that includes all the code, files and dependencies needed to run the containerized application. The images are often maintained in a repository that can be accessed by the container engine at runtime.

These days, most container images are based on the Open Container Initiative, which defines a set of standards for container formats and runtimes. When preparing to run an application, the container engine retrieves a copy of the container image and uses it to instantiate one or more containers. To update an application, a developer modifies the application's container image and then redeploys the image so it can be used to instantiate new containers.

Most containerized environments rely on an orchestration platform such as Kubernetes to manage container deployments. Orchestration platforms make it easier and more efficient to deploy, manage and scale containerized environments. They're particularly important for large-scale deployments, which can include thousands of containers. Orchestrators make it possible to automate many of the operations required to implement and maintain containerized applications.

Application containerization is often used for microservices and distributed applications. This is possible because each container operates independently of others and uses minimal resources from the host. The microservices communicate with each other through application programming interfaces. An orchestration tool can automatically scale up the containers to meet rising demand for application components, while at the same time distributing the workload to balance application traffic.

App containers vs. virtual machines

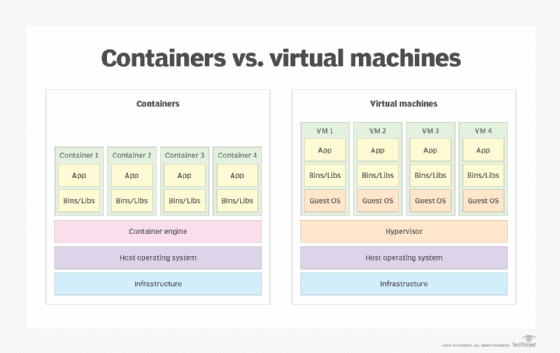

Application containers are often compared to VMs. They're both a form of virtualization that provides isolated environments for running applications, while better utilizing the underlying physical resources.

However, a virtual machine is not nearly as lightweight as a container because it runs its own guest OS. In fact, a VM looks like a physical machine when viewed from the outside. Virtual machines make it possible to host different operating environments on the same physical machine. For example, an organization might run a Linux VM alongside a Windows VM on the same server. Because of the guest OS, however, the VM also comes with much more overhead than an application container.

Virtual machines are hosted on server virtualization platforms. At the heart of this platform is the hypervisor, which sits on top of the host OS or is integrated into the OS. It abstracts the underlying hardware. The VMs do not connect to the host kernel like containers. In fact, they operate in isolation from the underlying system. The advantage here is that VMs provide greater security than containers. However, they also consume more resources and require more OS licenses than a containerized setup.

Application containers consume fewer resources than a comparable deployment on virtual machines. Containers share resources without a full operating system to underpin each app. Not only do containers use resources more efficiently, but they also make it possible to run more applications on a single server than with VMs. That said, these benefits also come with greater security risks.

For that reason, many IT teams and cloud providers deploy their containers within VMs. This means that a single server can host multiple VMs, perhaps running different OSes, with each VM supporting multiple containers. Despite these additional layers, however, the containers still share the same physical resources, but they rely on the VM's guest kernel. This approach offers better protection because of the additional isolation afforded by the VMs, although it also comes with greater complexity and overhead.

What is a system container?

Another type of container is the system container. The system container performs a role similar to virtual machines but without hardware virtualization. A system container, also called an infrastructure container, runs its own guest OS. It includes its own application libraries and execution code. System containers can host application containers.

Although system containers also rely on images, the container instances are generally long-standing and not momentary like application containers. An administrator updates and changes system containers with configuration management tools rather than destroying and rebuilding images when a change occurs. Canonical Ltd., developer of the Ubuntu Linux operating system, leads the LXD, or Linux container hypervisor, system containers project. Another system container option is OpenVZ.

Types of app containerization technology

The most common app container deployments have been based on Docker, specifically the open source Docker Engine and containers based on the RunC universal runtime. However, a number of Docker alternatives have also emerged, including Podman, Containerd and Linux LCD. For container orchestration, IT teams often use tools such as Kubernetes, Docker Swarm or Red Hat OpenShift, although there has been a growing number of other orchestration tools available on the market.

There are a variety of containerization products and services on the market, including those from the leading cloud service providers:

- Apache Mesos. Mesos is an open source cluster manager that handles workloads in a distributed environment through dynamic resource sharing and isolation. It is suited for the deployment and management of applications in large-scale clustered environments. The platform includes native support for launching containers with Docker and AppC images.

- Google Kubernetes Engine. Kubernetes Engine is a managed, production-ready environment for deploying containerized applications. It enables rapid app development and iteration by making it easy to deploy, update and manage applications and services.

- Amazon Elastic Container Registry (ECR). This Amazon Web Services product stores, manages and deploys Docker images. Amazon ECR hosts images in a highly available and scalable architecture, letting developers dependably deploy containers for their applications.

- Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS). AKS is a managed container orchestration service based on the open source Kubernetes system. AKS is available on the Microsoft Azure public cloud. Developers can use AKS to deploy, scale and manage Docker containers and container-based applications across a cluster of container hosts.

Choosing a platform for containerization

When selecting a platform for containerization, development teams should consider several important factors:

- Application architecture. The focus should be on the application architecture decisions to be made, such as whether the applications are monolithic or microservices as well as whether they're stateless or stateful.

- Workflow and collaboration. Consider the changes to the workflows and whether the platform will enable easy collaboration among stakeholders.

- DevOps. Consider the requirements for using the self-service interface to deploy apps through the DevOps pipeline.

- Packaging. Consider the format and tools to use the application code, dependencies, containers and container dependencies.

- Monitoring and logging. Ensure that the available monitoring and logging options meet requirements and work with current development workflows.

Deploying containerized applications can also impact IT teams, especially those who are involved with DevOps initiatives. For this reason, the teams should consider several important factors before deploying their containerized apps:

- Architectural needs of applications. Ensure that the platform meets the architectural needs of the application as well as the storage needs for stateful applications.

- Legacy application migration. The platform and tooling around the platform must support any legacy applications that must be migrated.

- Application updates and rollback strategies. Work with the developers to define application updates and rollbacks to meet the service-level agreement.

- Monitoring and logging. Put plans in place for the right infrastructure and application monitoring and logging tools to collect a variety of metrics.

- Storage and network. Ensure that the necessary storage clusters, network identities and automation to handle the needs of any stateful applications are in place.

History of application containerization

Container technology was first introduced in 1979 with Unix version 7 and the Chroot system. Chroot ushered in the beginning of container-style process isolation by restricting the file access of an application to a specific directory -- the root -- and its children. A key benefit of chroot separation was improved system security. An isolated environment couldn't compromise external systems if an internal vulnerability was exploited.

FreeBSD introduced the jail command into its operating system in March 2000. The jail command was much like the chroot command. However, it included additional process sandboxing features to isolate file systems, networks and users. FreeBSD jail provided the ability to assign an IP address, configure custom software installations and make modifications to each jail. However, applications within the jail had limited capabilities.

Solaris containers, which were released in 2004, created full application environments via Solaris Zones. Zones let a developer give an application full user, process and file system space as well as access to the system hardware. But the application could see only what was within its own zone.

In 2006, Google launched process containers designed for isolating and limiting the resource use of a process. The process containers were renamed control groups (cgroups) in 2007 so as not to be confused with the word container.

Then, in 2008, cgroups were merged into Linux kernel 2.6.24. This led to the creation of what's now known as the LXC (Linux containers) project. LXC provided virtualization at the OS level by enabling multiple isolated Linux containers to run on a shared Linux kernel. Each of these containers had its own process and network space.

Google changed containers again in 2013 when it open-sourced its container stack as a project named Let Me Contain That For You (LMCTFY). Using LMCTFY, developers could write container-aware applications. This meant that they could be programmed to create and manage their own sub-containers. In 2015, Google stopped work on LMCTFY, choosing instead to contribute the core concepts behind LMCTFY to the Docker project Libcontainer.

Docker was released as an open source project in 2013. With Docker, containers could be packaged so that they could be moved from one environment to another. Initially, Docker relied on LXC technology. However, LXC was replaced with Libcontainer in 2014. This let containers to work with Linux namespaces, Libcontainer control groups, AppArmor security profiles, network interfaces, firewall rules and other Linux capabilities.

In 2017, companies such as Pivotal, Rancher, AWS and even Docker changed gears to support the open source Kubernetes container scheduler and orchestration tool.

Further explore the evolution of containers over the last two decades, and follow these tips to prepare for for successful container adoption. Explore the advantages of containers over virtual machines for storage and why you should use containers vs. VMs in a modern enterprise. See how microservices and containers work, apart and together.