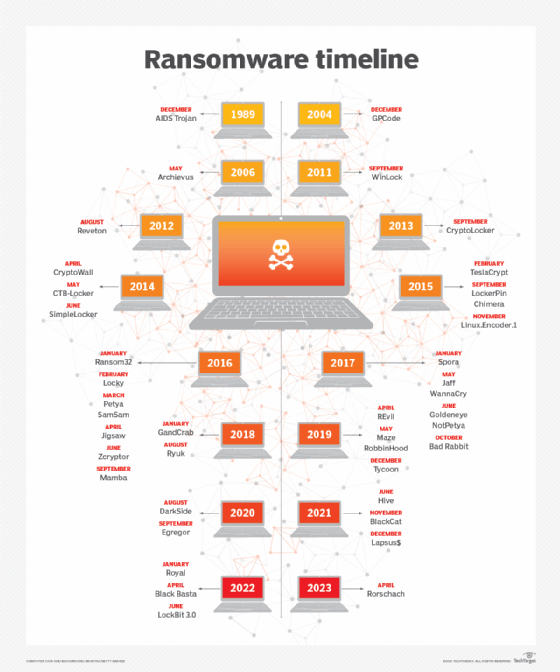

Types of ransomware and a timeline of attack examples

There are eight main types of ransomware but hundreds of examples of ransomware strains. Learn how the ransomware types work, and review notable ransomware attacks and variants.

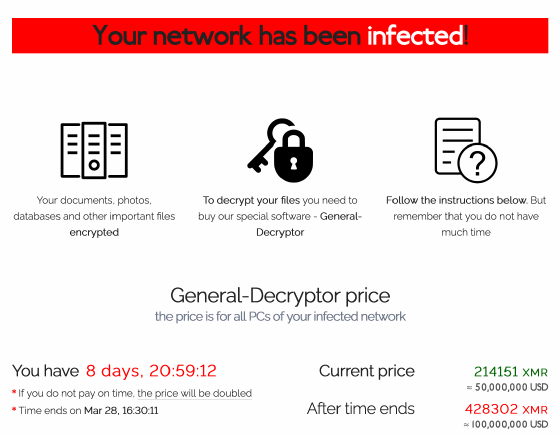

Ransomware is one of the most effective strategies for attacking businesses, critical infrastructure and individuals. This type of malware infects computers and prohibits or severely restricts users and external software from accessing devices or entire systems until ransom demands are met.

To understand the concept, let's look at various types of ransomware and then a timeline with examples of specific ransomware strains and their effect on the security landscape.

Types of ransomware

Ransomware can be split into two general categories: how it is delivered and what it impacts. Delivery includes ransomware as a service (RaaS); automated delivery -- but not as a service; and human-operated delivery, which is the most expensive but most effective method.

In terms of impact, ransomware can affect the availability of data -- for example, encrypting the data and requesting the victim pay to get the decryption key; destroying the data -- for example, data is deleted if a payment is made or, in some cases, not made; and disrupting access -- for example, a service is rendered unusable via a DDoS attack or locking of a system. Exfiltration is another effect, where data is leaked with a threat to make it public if a ransom is not paid.

This article is part of

What is ransomware? How it works and how to remove it

Many other terms further describe the types of ransomware, including the following:

- Locker ransomware blocks access to computer systems entirely. This variant uses social engineering techniques and compromised credentials to infiltrate systems. Once inside, threat actors block users from accessing systems until a ransom is paid. A pop-up on the victim's screen may appear saying, "Your computer was used to visit websites with illegal content. To unlock your computer, you must pay a $100 fine," or, "Your computer has been infected with a virus. Click here to resolve the issue."

- Crypto ransomware is more common and widespread than locker ransomware. It encrypts all or some files on a computer and demands a ransom from the victim in exchange for a decryption key. Some newer variants also infect shared, networked and cloud drives. Crypto ransomware spreads through various means, including malicious emails, websites and downloads.

- Scareware is a tactic attackers use to scare victims into believing their devices are infected with malware when they aren't actually infected. Pop-up windows with alarming messages -- often with a sense of urgency -- inform users to pay a fee or purchase software to fix the malware. Paying sometimes resolves the issue, but sometimes, the purported software fix contains malware itself, which then steals data and deploys more ransomware.

- Extortionware, also known as leakware, doxware and exfiltrationware, involves malicious actors stealing data and threatening to publish it unless a ransom is paid -- extorting the data owner. Whereas ransomware historically involves attackers demanding a ransom or else data is inaccessible, extortionware puts added pressure on victims -- if they don't pay the ransom, data is released to the public.

- Wiper malware, sometimes called wiperware or data wipers, is not necessarily a type of ransomware, but it targets data like many varieties of ransomware. Instead of encrypting or locking files, however, wiper malware erases -- or wipes -- data from victims' systems. The aim is not financial gain, as in most ransomware types, but to destroy evidence, sabotage a victim or disrupt operations during a cyberwar. Many strains of wiperware use ransomware tactics.

- Double extortion ransomware encrypts files and exports data to blackmail victims into paying a ransom. With double extortion ransomware, attackers threaten to publish stolen data if their demands are not met. This means that, even if victims can restore their data from backup, the attacker still has power over them. Paying the ransom doesn't guarantee protection of the data because the attackers still possess the stolen data.

- Triple extortion ransomware adds another layer to a double extortion ransomware attack. In some triple extortion ransomware attacks, business operations are disrupted with a DDoS attack. The third extortion could also involve attackers intimidating a victim's employees, clients, suppliers or partners and even threatening to expose their data and asking them to pay ransoms themselves.

- RaaS is not a type of ransomware per se -- rather a delivery model -- but is often included in lists of ransomware types. It involves perpetrators renting access to a ransomware strain from the ransomware author, who offers it as a pay-for-use service. RaaS creators host their ransomware on dark net sites and allow criminals to purchase it as a subscription -- much like a SaaS model. The fees depend on the ransomware's complexity and features, and generally, there's an entry fee to become a member. Once members infect computers and collect ransom payments, a portion of the ransom is paid to the RaaS creator under previously agreed-upon terms.

Examples of ransomware strains

A timeline of some of the most notable examples of ransomware from the past 30-plus years follows.

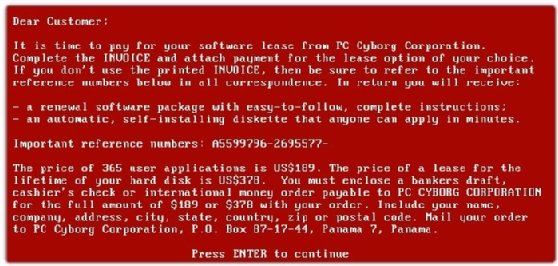

December 1989: AIDS Trojan

The first documented ransomware was created by Joseph Popp, a Harvard-educated biologist. Popp mailed 20,000 floppy disks containing the AIDS Trojan, also known as the PC Cyborg virus, to researchers across the globe. Recipients were led to believe the disks contained Popp's AIDS research, but once opened, victims' files were encrypted with simple symmetric cryptography. Victims were told to send $189 to a P.O. box in Panama to decrypt the files. Popp, whose motives remain a mystery, has been credited as the father of ransomware.

December 2004: GPCode

After a 15-year lull, GPCode marked the beginning of ransomware in the internet era. The malware, spread via email, encrypted victims' files and renamed them Vnimanie, meaning attention in Russian. Unlike many of today's ransomware attacks, GPCode's authors focused on volume rather than individual payouts, sending an exorbitant number of malicious emails and demanding $20 to $70 ransoms.

May 2006: Archievus

Archievus was the first ransomware to use a 1,024-bit RSA encryption key. It targeted Windows systems and spread via malicious URLs and spam emails. The malware targeted computers' "My Documents" folders. Once folders were encrypted, victims were directed to an online store -- only after victims made a purchase would they receive a password to unlock their files. While the RSA encryption key was difficult to crack, Archievus was quickly abandoned once it was discovered the attackers used the same password to lock all files.

September 2011: WinLock

WinLock was the first locker ransomware to hit the headlines. The nonencrypting ransomware infected users via a malicious website. Victims were instructed to purchase a $10 text message code. After inputting the code into their devices, victims were prompted to call an alleged toll-free number. The calls were rerouted, however, and the victims incurred additional fees.

August 2012: Reveton

Reveton was a form of financial ransomware delivered via drive-by-download attacks. Once infected, a pop-up alert that purported to be from law enforcement claimed the victim committed a crime, such as downloading pirated software, and threatened imprisonment if the "fine" was not paid via a money payment service. Later Reveton variants used victims' webcams, requested bitcoin payments, distributed password-stealing malware, and infected Mac and mobile OSes.

September 2013: CryptoLocker

CryptoLocker is one of the first examples of sophisticated ransomware that combined locker and crypto ransomware. It locked users out of their devices and used a 2,048-bit RSA key pair to encrypt systems and any connected drives and synced cloud services. This increased the chances of payment because, even if the victim removed the lock, access wouldn't be restored because the system was encrypted. CryptoLocker spread via malicious attachments in spam FedEx and UPS tracking notices, as well as infected websites. Attackers requested a $300 ransom to unlock devices. The ransomware reportedly earned $27 million in ransom payments in its first two months.

_mobile.jpg)

April 2014: CryptoWall

Dell Secureworks Counter Threat Unit called CryptoLocker copycat CryptoWall "the largest and most destructive ransomware threat on the internet" in August 2014. The ransomware never became as well known as its predecessor, however. In the strain's first six months, it infected 635,000 systems and earned more than $1.1 million in ransom payments. CryptoWall spread via phishing emails and malicious advertisements on legitimate websites. In many instances, victims could have avoided the attack if they had simply updated their software and backed up their servers.

May 2014: CTB-Locker

Curve-Tor-Bitcoin (CTB)-Locker used elliptic curve cryptography to encrypt victims' files and the Tor browser to obfuscate its communications activities. Once infected via malicious emails and downloads, victims were prompted to pay a ransom via bitcoin. CTB-Locker was one of the first ransomware strains to use multilingual notices to inform victims of infection. It also marked the start of the widespread use of cryptocurrency for ransom payments.

June 2014: SimpleLocker

SimpleLocker, sometimes referred to as Simplocker, was the first ransomware to target Android devices. The Trojan scanned SD cards and encrypted users' images, documents and videos. Later versions could access victims' cameras. It was known for collecting devices' phone numbers, model numbers and manufacturers. Like CTB-Locker, SimpleLocker used Tor to prevent being traced. Attackers demanded a ransom in exchange for a password to regain access.

February 2015: TeslaCrypt

TeslaCrypt got its start targeting computer gamers. Its first iteration could only encrypt files smaller than 268 MB. Attackers demanded $500 in ransom and threatened to double the fee if victims delayed paying. In 2016, the cyber gang behind TeslaCrypt released a master key, which enabled victims to decrypt their files for free.

September 2015: LockerPin

LockerPin was the first PIN-locking mobile ransomware to target Android OS devices. It infected users after being downloaded from third-party app stores. Unlike its SimpleLocker predecessor, which was the first to encrypt files on mobile devices, LockerPin could override administrative privileges, stop antivirus programs running on the device and change the victim's PIN. Even if the $500 ransom were paid, attackers were unable to unlock victims' devices because the PINs were randomly generated and unknown even to the attackers.

September 2015: Chimera

The Chimera ransomware was one of the first strains that threatened to leak victims' data if a 2.5 bitcoin ransom wasn't paid. It remains unclear, however, if attackers ever stole the files' data or if the threats were idle. Chimera spread via emails containing malicious Dropbox links. In July 2016, rival ransomware group Petya released 3,500 Chimera decryption keys. Other Chimera decryptors are also available.

November 2015: Linux.Encoder.1

Linux.Encoder.1 was the first ransomware Trojan to target Linux-based machines. After exploiting a flaw in the e-commerce Magento platform, the Trojan encrypted MySQL, Apache, and home and root folders. Attackers demanded a single bitcoin in exchange for the decryption key. Patching systems against the Magento flaw prevented users from becoming victims.

January 2016: Ransom32

Ransom32 was the first JavaScript ransomware. This made it a cross-platform, "write once, infect all" ransomware that could infect Windows, Linux and Mac OSes.

February 2016: Locky

Locky ransomware used the Necurs botnet to send phishing emails with Word or Excel attachments that contained malicious macros. It encrypted files on Windows OSes. A June 2016 version could detect if the malware was being run in a sandbox, and a July 2016 variant could encrypt files offline. Locky resurfaced in September 2017 in an attack where 23 million phishing messages were sent in a 24-hour window.

March 2016: Petya

Petya was labeled the "next step in ransomware evolution" by Check Point researchers due to its ability to overwrite the master boot record (MBR) and encrypt the master file table (MFT), which logs the metadata and the physical and directory location of all files on a device. These three steps locked victims out of their system. Petya infected Windows-based systems through phishing emails.

March 2016: SamSam

SamSam is notable for its manual operations. After identifying their victims, attackers use brute-force and legitimate Windows tools to infect specific devices. After the ransomware executes, a bitcoin ransom is demanded. Later versions incorporated additional complexity, encryption and obfuscation techniques. Targets and victims included healthcare, education and critical infrastructure. SamSam was used in the 2018 attacks against the city of Atlanta and the Colorado Department of Transportation. A 2018 Sophos report found the ransomware has brought in $6 million since its creation.

April 2016: Jigsaw

Victims of the Jigsaw ransomware, which infected systems via malicious emails, were confronted by a photo of Billy, the puppet from the Saw film franchise, and a countdown timer. If the $150 ransom wasn't paid in an hour, one of the victim's files was deleted. Each hour that went by, the number of files deleted increased. If victims attempted to restart their devices, up to 1,000 files were instantly deleted. A decryption key has since been released.

June 2016: Zcryptor

Zcryptor was one of the first examples of a cryptoworm, a hybrid computer worm and ransomware. It self-duplicated to copy itself onto external connected devices and networks. Zcryptor encrypted files until a ransom of 1.2 bitcoin was paid to the attackers; after four days, the ransom increased to 5 bitcoin.

September 2016: Mamba

Mamba, also known as HDDCryptor, was a disk-encrypting ransomware that spread using a legitimate DiskCryptor encryption tool. It was notably used in an attack on the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. When railway passengers tried to purchase tickets, a message appeared on the screen notifying them of the attack. Reports have suggested Mamba exploited an unpatched Oracle server program, while a simple system update could have prevented the attack.

January 2017: Spora

Spora, named after the Russian word for spore, is notable for both its ability to work offline and sophisticated payment system. It spreads through phishing emails containing malicious zip attachments. Once downloaded, Spora encrypts files using a combination of AES and RSA algorithms. Spora's offline component enables the malware to distribute without generating traffic to other online servers in the network. In August 2017, an upgraded version of Spora was released that enabled attackers to steal browsing information and record keystrokes.

May 2017: Jaff

Jaff was detected a day before the infamous WannaCry attack. While it mimicked Locky, it was far less sophisticated. Jaff used the Necurs botnet to spread roughly 5 million malicious emails per hour. Attackers demanded $3,300 in bitcoin -- a much higher ransom than other variants.

May 2017: WannaCry/WannaCrypt

WannaCry was used during the May 2017 global cyber attack against systems in 150 countries. In May 2019, it was reported the ransomware spread to nearly 5 million vulnerable devices. The self-replicating cryptoworm affected high-profile organizations, including the U.K.'s National Health Service, FedEx, Honda and Boeing. Also known as WannaCrypt, WannaCryptor and Wanna Decryptor, it spread via the National Security Agency-leaked EternalBlue exploit, a vulnerability in legacy versions of Server Message Block. Microsoft had released a patch in March 2017, but it was not widely updated. WannaCry was touted as the biggest ransomware attack to date in 2017.

June 2017: Goldeneye

Goldeneye, a variant of Petya, is often called WannaCry's sibling. It spread via phishing and encrypted individual files, the MBR and the MFT. Like WannaCry, it propagated via EternalBlue. Infected devices crashed, restarted and then displayed a ransom pop-up screen. A decryptor became available the next month.

June 2017: NotPetya

The Petya variant dubbed NotPetya is considered ransomware, but as wiperware, it focuses on destroying files rather than collecting money. Like Petya, it encrypts the MBR and the MFT. Unlike Petya, after encryption, it destroys the device's content. Even if victims pay the ransom, they never get their files back. NotPetya uses multiple attack vectors, including legitimate software tools.

October 2017: Bad Rabbit

Bad Rabbit, a variant of NotPetya, uses fake Adobe Flash installer advertisements to target victims. Like Petya, Bad Rabbit exploits EternalBlue and encrypts the MBR. Once a device is infected, a message appears demanding 0.05 bitcoin. If victims don't pay within 40 hours, the ransom increases.

January 2018: GandCrab

GandCrab was the first RaaS variant to demand payments in Dash cryptocurrency. It used a .bit top-level domain, which is not sanctioned by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, to ensure secrecy. GandCrab spread through emails, exploit kits and other malware campaigns. It was responsible for more than 50% of the ransomware market by August 2018. In 2019, the ransomware gang behind GandCrab retired and released a decryption tool.

August 2018: Ryuk

Ryuk, named after a manga character, was one of the first variants to encrypt network drives, delete shadow copies and disable Windows System Restore, making it impossible for victims to recover without external backups or rollback technology. Ryuk is distributed by phishing emails containing malicious Microsoft Office documents. It was used in an attack against Tribune Publishing Company in December 2018. In 2019 and 2020, it was used in several attacks against healthcare organizations. Targets and victims also include governments, school systems, and other public and private sector companies.

April 2019: REvil

REvil, also known as Sodin and Sodinokibi, may be related to 2018's GandCrab. The two strains have striking similarities and were deployed together on victims' systems in early attacks before GandCrab's retirement. Early attacks exploited an Oracle WebLogic vulnerability and a Windows zero-day vulnerability. Later exploits infiltrated systems through phishing, Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) flaws, VPN attacks and supply chain attacks. It has a dark web leak site, known as the Happy Blog. REvil was used in notable attacks against Acer, JBS USA and Kaseya. The ransomware group went offline in July 2021 but reemerged in September 2021. A universal decryptor was released in September 2021 for victims of attacks pre-July 13, 2021.

May 2019: Maze

Maze, a variant of ChaCha, spread via spam emails, RDP attacks and exploit kits. It is one of the first examples of double extortion ransomware. In June 2019, Maze operators announced the creation of a cartel of cybercrime gangs. Maze shuttered operations in November 2020.

May 2019: RobbinHood

RobbinHood infiltrates victims' networks through phishing schemes, RDP attacks or other Trojans, sometimes abusing CVE-2018-19320, a Gigabyte kernel driver vulnerability. It disables services and protective programs, disconnects network shares, deletes shadow copies, clears event lots and disables Windows automatic repair. RobbinHood's ransom demands range from 3 to 13 bitcoin. The ransomware strain was notably used in attacks against the cities of Baltimore and Greenville, N.C., neither of which paid the ransom. The city of Baltimore reportedly paid $18 million in recovery costs, as opposed to a $114,000 ransom.

December 2019: Tycoon

Tycoon targets Windows and Linux environments at educational institutions and software companies. BlackBerry researchers said it is the first ransomware strain to use the Java image, or JIMAGE, format to create and deliver a customized malicious Java Runtime Environment build. Once inside a network, Tycoon disables antimalware programs and can remain hidden for months before encrypting file servers and demanding a ransom. A decryptor key was posted online, which decrypts some, but not all, affected systems.

August 2020: DarkSide

DarkSide, the malware used in the Colonial Pipeline attack in early May 2021, is RaaS that targets high-profile victims. It uses double extortion, command and control via Tor, and advanced obfuscation techniques, among other stealth tactics. Later in May 2021, the ransomware gang announced its operations were suspending following pressure from the U.S. government. BlackMatter, a ransomware group that emerged in July 2021, has noted similarities to the DarkSide and REvil gangs.

September 2020: Egregor

Egregor, a variant of the Sekhmet ransomware, is RaaS that many speculate to be former Maze affiliates. It was used in attacks against Barnes & Noble and Kmart, among others. Egregor is a double extortion strain that publicly shames its victims. Once the ransom is paid, the attackers decrypt the victims' systems and offer victims advice on how the company can better protect its network and avoid future attacks. An undisclosed number of Egregor affiliates were arrested in February 2021. Around the same time, the ransomware gang's infrastructure went offline.

June 2021: Hive

The Hive ransomware group emerged midyear, initially targeting healthcare organizations and later retailers, critical infrastructure, IT companies and others. The multiplatform ransomware was originally written in Golang, but later 2022 variants used Rust. It infiltrated systems via RDP, VPN and other remote network connection protocols, as well as phishing scams and exploiting Exchange Server vulnerabilities. CISA reported that, by November 2022, Hive had 1,300 victim organizations and received around $100 million in ransom payments. In January 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice announced it had seized Hive's servers. In July 2022, the FBI said it had captured Hive decryption keys and provided them to victims worldwide.

November 2021: BlackCat

Also known as AlphaV and ALPHV, BlackCat is one of the first ransomware strains written in the Rust programming language, enabling it to evade detection by many security tools. It was also one of the first strains to use triple extortion techniques, adding a DDoS component to its attacks. BlackCat, reportedly related to BlackMatter, is responsible for attacks on Oiltanking GmbH, Swissport, Western Digital, the Austrian state of Carinthia, the city of Alexandria, La., and more. It commonly exploits flaws in Exchange Server, SonicWall and Windows.

December 2021: Lapsus$

The Lapsus$ threat group made headlines for a December 2021 attack against the Brazilian Ministry of Health. The group does not use an affiliate model to operate RaaS. Rather, its members complete every stage of the breach using social engineering, stolen credentials, data and public extortion, and lateral movement attacks. It uses the Telegram messaging app to communicate with the public, its victims and potential recruits. The group is responsible for attacks on Okta, Nvidia, Samsung, T-Mobile, Microsoft and Uber. In March 2022, seven people were arrested by London police in connection with Lapsus$.

January 2022: Royal

The Royal ransomware group, known as Zeon before rebranding, originally used BlackCat's encryptor and later used ransom notes similar to Conti's before using its own encryptor for ransom notes. Royal encrypts small amounts of data to avoid detection by antimalware and other threat detection software. This enables it to carry out attacks quickly due to it encrypting less data. Cybereason analysts, who released research on Royal, noted its tactics were "efficient and evasive."

April 2022: Black Basta

Black Basta RaaS became notorious for breaching nearly 100 organizations from its inception through October 2022. It became the second most active ransomware after LockBit, accounting for 9% of all ransomware. Black Basta uses double extortion ransomware, and its attack techniques include the QakBot banking Trojan and PrintNightmare exploits. Its victims include the American Dental Association, electrification and automation company ABB, Yellow Pages Canada, German wind farm operator Deutsche Windtechnik and British outsourcing company Capita.

June 2022: LockBit 3.0

LockBit RaaS first emerged in September 2019 as the ABCD Virus. LockBit 2.0 was first detected in 2020 and 3.0 in June 2022, with the tagline "Make Ransomware Great Again." Also known as LockBit Black, 3.0 shares similarities with BlackMatter and BlackCat ransomware. LockBit 3.0 is notable for its addition of a bug bounty program. LockBit operators said rewards for finding bugs in its code started at $1,000, with a $1 million payout to anyone who could dox LockBit's owners. CISA reported LockBit was the most used ransomware variant in the world in 2022.

April 2023: Rorschach

Check Point researchers called Rorschach one of the fastest ransomware variants ever observed based on its speed of encryption. Though it has similarities to Babuk, DarkSide, LockBit and Yanluowang, researchers have not been able to confidently connect it to any other ransomware strains or groups. It was dubbed Rorschach because "each person who examined the ransomware saw something a little bit different." The locker ransomware is partly autonomous, is self-propagating and uses hybrid cryptography, meaning it only encrypts part of a file instead of an entire file. This enables it to achieve fast speeds. In Check Point's tests, 22,000 files were encrypted with Rorschach in an average of four minutes and 30 seconds. LockBit, previously named one of the fastest encryptors, took seven minutes.